Wolfgang Weingart — In His Own Words

“I was born in a February. For the first thirteen years I lived in a beautiful valley near Lake Constance, the Salem Valley, in the southern-most part of Germany close to the Swiss border. It was the most important time of my life, and I have come to understand how the earliest years of life are the most decisive ones for individual and professional development. They are made of dreams and feelings only a child can experience.” [1]

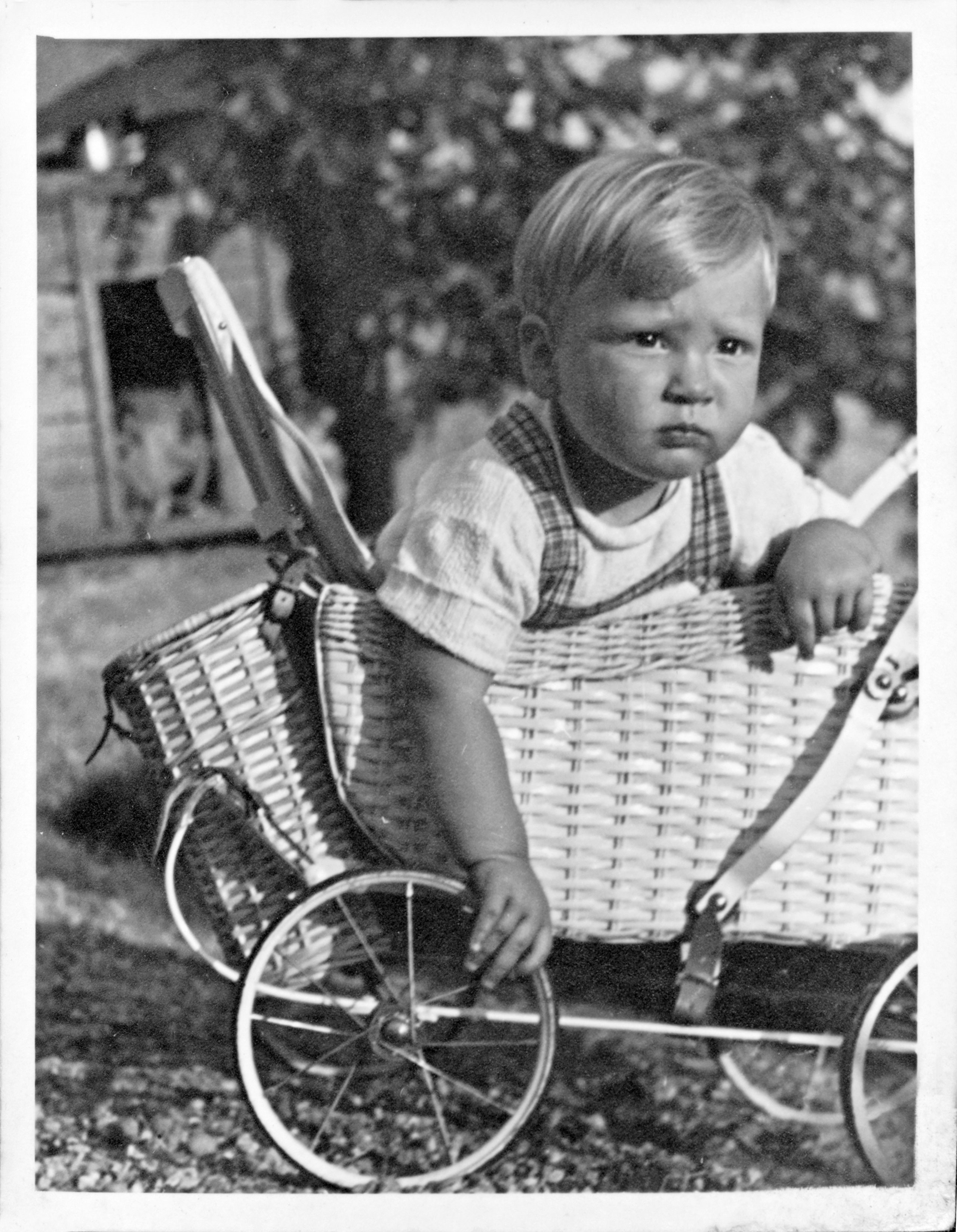

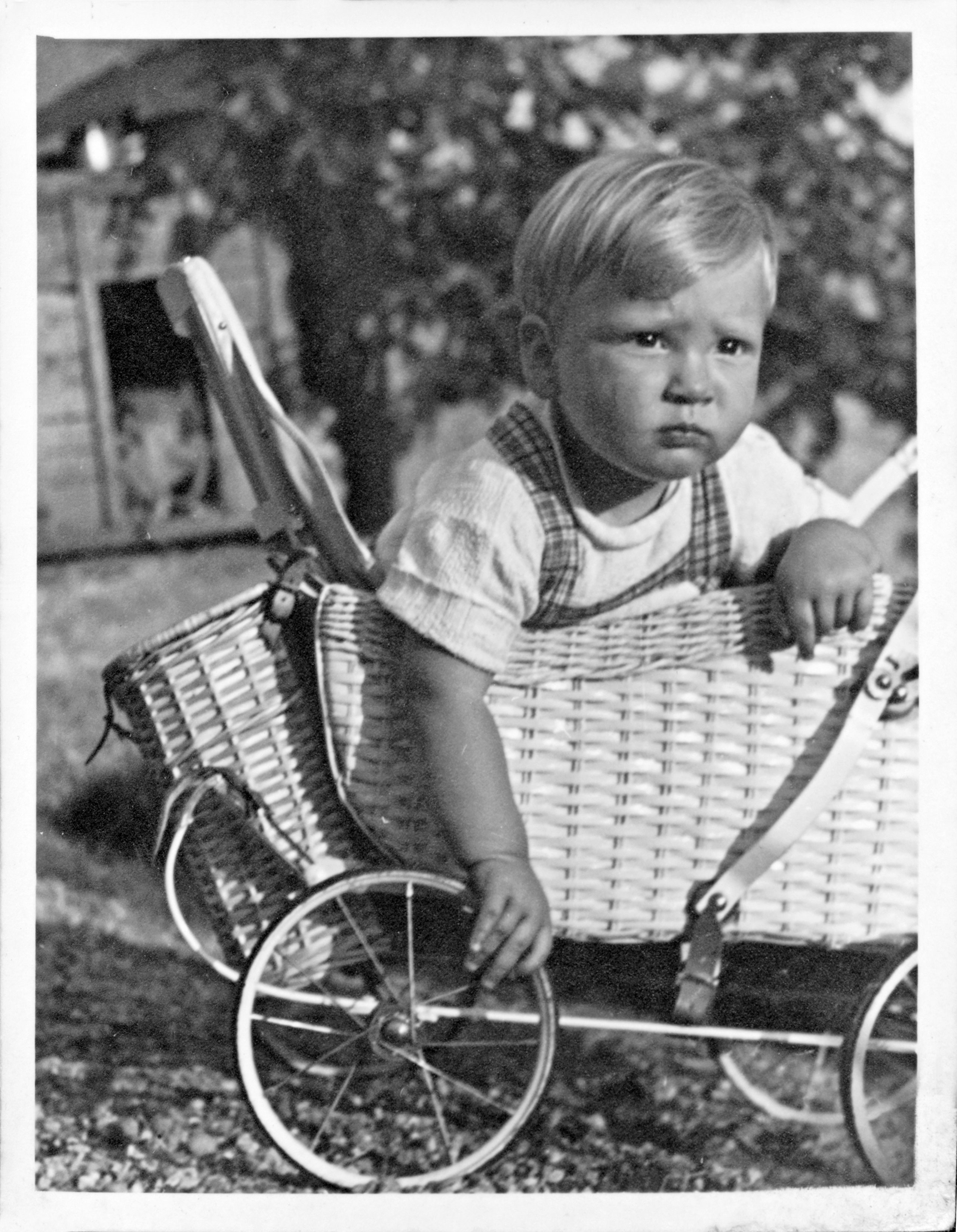

Weingart in his early days.

With these words Wolfgang Weingart slowly draws us into his autobiographical masterpiece ‘Typography My Way to Typography — Mein Weg zur Typographie’. Weingart began work on this book in the autumn of 1994, which was then published six years later in 2000. The 520-page monolithic monograph contains a personal retrospective of his early life, artistic and typographical works, as well as his personal development as a designer. An authentic documentation of this gentlemanly provocateur, it is an invaluable source of inspiration for students and teachers of typography and graphic design.

In ‘My Way to Typography’, Weingart tells the story how his very early years were dramatically affected by World War II: “One night in the early spring of 1944, eleven months before the end of the Second World War, came the warning of another possible Allied attack. On the onset of the air raid, my mother and I headed in a frenzy for the deep, dark vaulted cellar to hide once again among the familiar cupboards, crates, and other curious contraptions. One of the most memorable ones was a wooden construction that was always in the same spot. It was the machine with which my mother made ice cream. The wooden tub held a cold mixture of natural ice and salt lick pieces that surrounded an internal steel vat with a built-in dasher to stir the cream. After thirty minutes of churning with the hand crank attached to the outside, the cream became cold and thick enough to eat.” [1]

As a child, this must have been a very comforting memory for him, every detail is crystal clear. And later in life, whenever dining out in the neighboring German towns with students and friends, Weingart would religiously order ice cream for dessert, topped off with a shot of locally distilled firewater — known in German as ‘Schnaps’ or ‘Träsch’. [2]

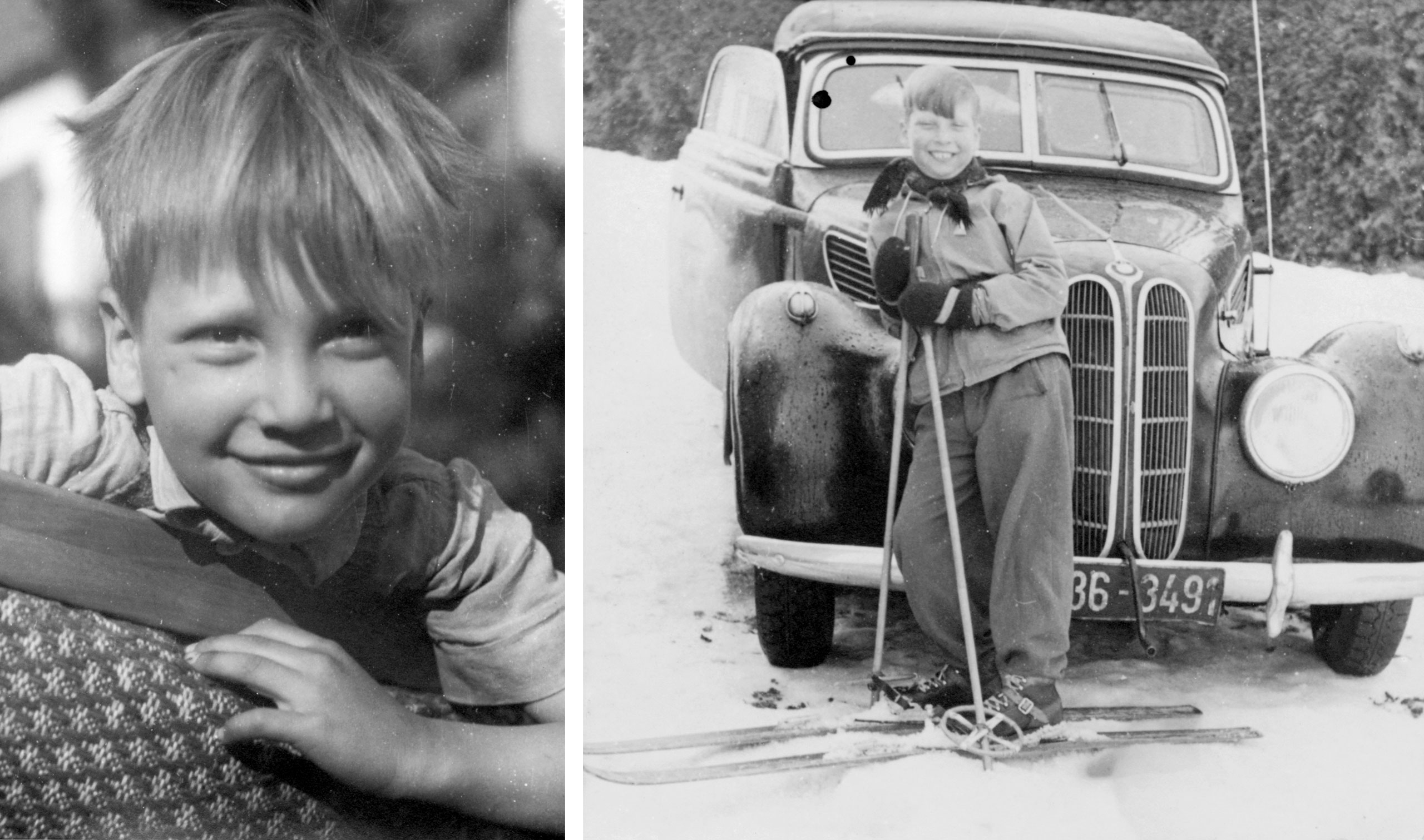

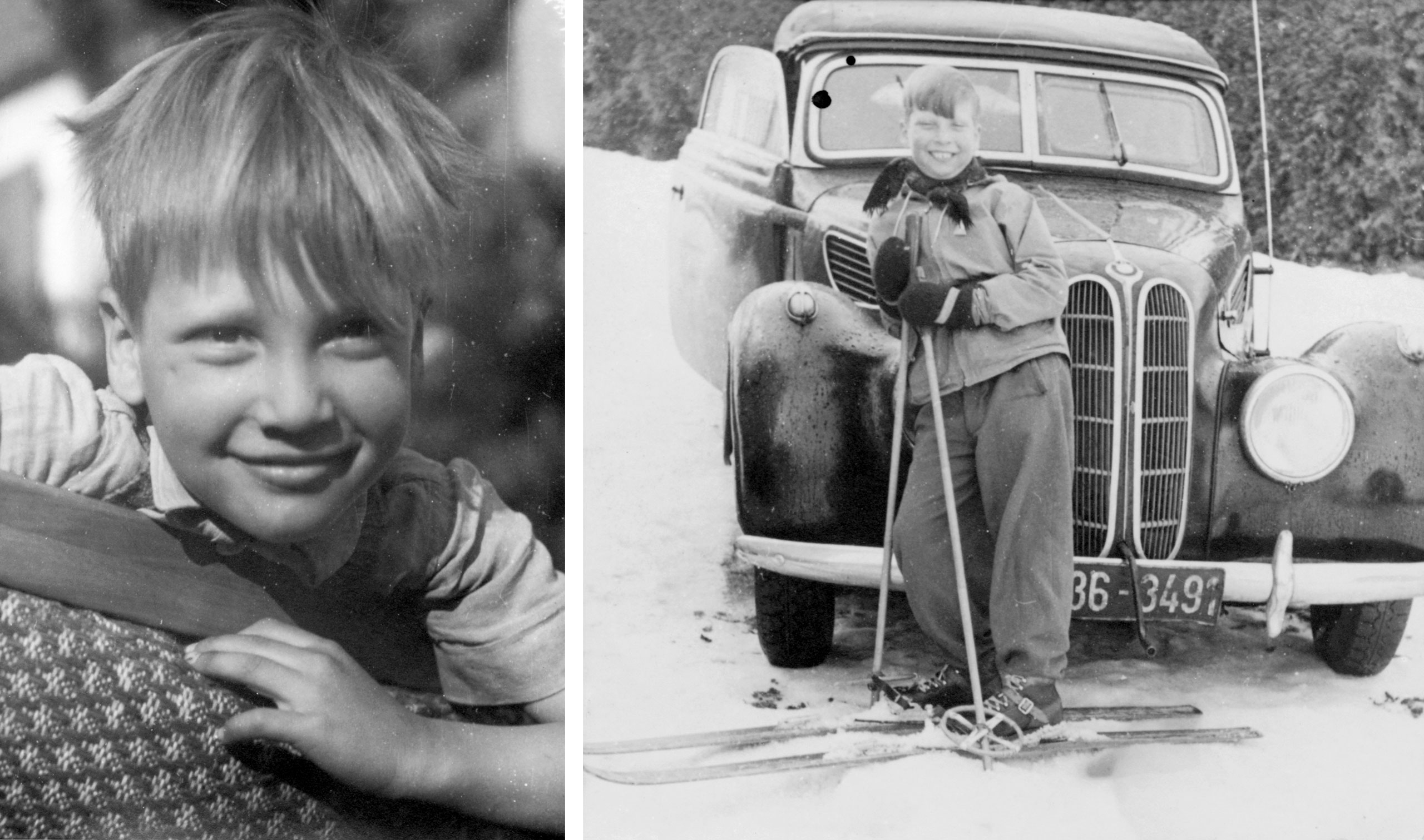

Weingart as a young boy, ready to hit the alpine slopes.

He vividly remembered the bombing and annihilation of the near-by town of Friedrichshafen in 1944 — precisely on April 28th — and was a witness to it’s dramatic aftermath. “Beyond the peaceful, silhouetted forest of our valley, a great pillar of fire mounted upwards and turned the nighttime skies to glowing red. Although only three years old and not realizing what had happened, I remember the fear like a permanent scar.” [1]

Weingart used his inner strength to heal from these traumatic experiences, to become resilient, to develop stability and learn to trust in his own beliefs. Many called him a rebel, but actually he was a survivor.

Wolfgang taking care a young deer.

In the spring of 1948, at the age of eight, he and his family moved into the castle of Salem, which was drenched in history: In 1098, it was established as an abbey of the Cistercians, a strict monastic order of the Catholic church according to the sixth century ‘Rule of Saint Benedict’. The residents were known as ‘black monks’, in reference to the colour of their religious habits, or costumes. As a result of the transition from church to state ownership, the abbey became a castle. What a dreamy place for a child’s imagination to develop!

Weingart’s mother was the resident physician at the castle and, besides having many chores to do, Weingart often entertained himself by spying on the aristocratic patients who visited his mother for medical treatments. “The keyholes to our rooms were just large and low enough for a small boy to comfortably observe the comings and goings of the international princes, princesses, duchesses, ladies, barons, and other honorable guests.” [1]

He and his mother however, lived in just two modest rooms of the castle, which were difficult to heat during the cold winter months, he remembered. Throughout his life, with a glint in his eye and a snicker on his face, he joked about the fact that he used to steal money from his mother — which finally ended on one occasion where he could not get out of bed for three days after being punished with “the dreaded wooden spoon”. Needless to say, he had a strict German upbringing, which later occasionally rubbed off on his style of teaching. [1] [2]

In 1954, he moved to Lisbon (Portugal) with his family and lived there for two years — “In contrast to war-stricken Germany, the foreign south embodied the fantasies of my childhood.” And upon visiting the nearby Spanish Mérida, his love for the Arabian culture started to bloom. His travels to the coastal city of Tangier (Morocco), with densely populated markets, mobs of veiled people and animals of all sorts, echoed his fantasy of how life must have been in the Middle Ages. According to Weingart, the cosmopolitan atmosphere with an abundance of shops with hand-lettered signs, custom tailors, and the tranquility of a relaxed city would later shape his design language.

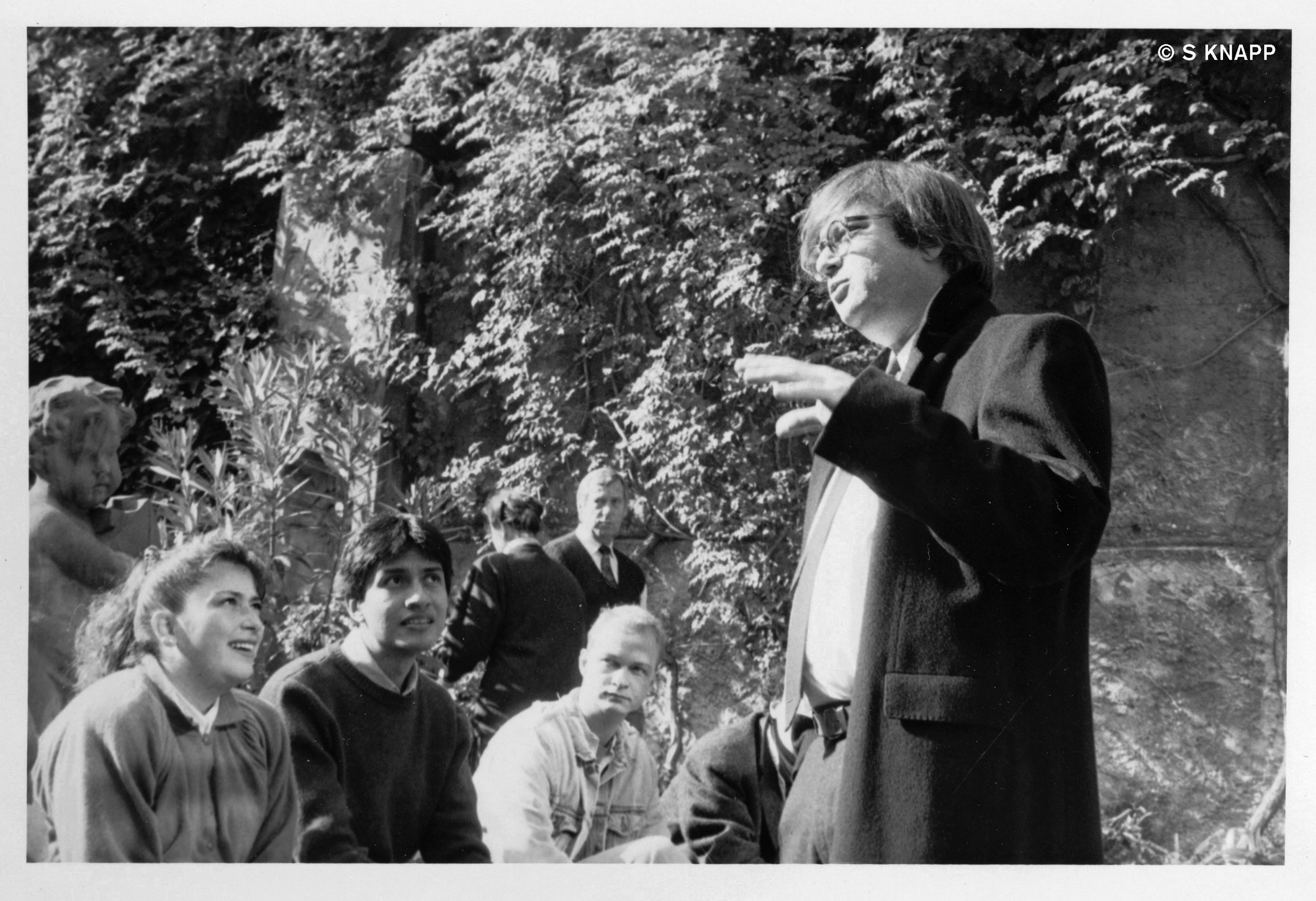

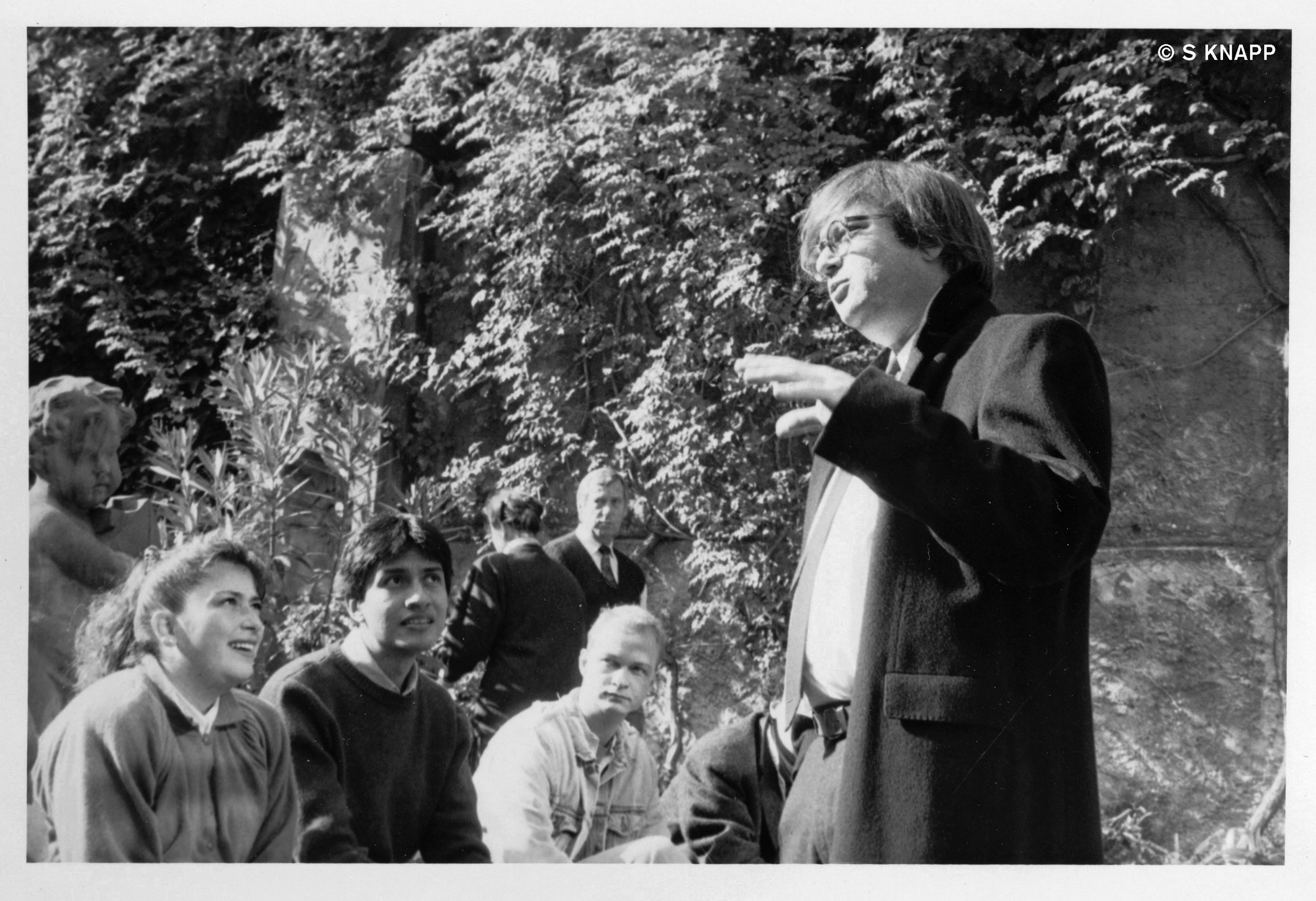

Weingart on a field trip to Colmar with his students, 1990.

Although he was restless not knowing which direction life would take him, or how he would later make a living from his artistic passions, he was grateful to his parents for always encouraging him and eventually sending him to art school. In 1958, at the age of seventeen, he began a two-year program of applied arts and design at the Merz Academy in Stuttgart. He studied colour and drawing and discovered his love for linoleum and woodcuts, hot metal type and other various printing techniques.

In his free time, Weingart would work on his own projects, and because he was on good terms with the head of the school’s printing shop, he was able to use the facilities as he pleased. He helped out printing the school’s letterheads, invoices, student ID cards and other administrational forms. All of these experiences contributed greatly to a fundamental understanding of printing, which he would then later apply to his typography classes at the ‘Schule für Gestaltung’ — the Basel School of Design.

Students and teachers of the Advanced Class for Graphic Design, 1990.

In 1960 he began an apprenticeship as a typesetter at the Ruwe printing house in Stuttgart. Little did he then know that this five hundred year-old tradition was about to see radical transformations. Weingart admitted he was fortunate “to have had well-informed teachers who encouraged intense discussions and lively debate.” And it was here that he learned about the new ‘Swiss typography’ and designers such as Karl Gerstner, Emil Ruder, Armin Hofmann, Siegfried Odermatt and Carlo Vivarelli. The Basel School of Design and the ‘Neue Grafik’ design magazine had earned worldwide fame. Karl-August Hanke, a consultant at Ruwe, was one of Armin Hofmann’s first students at the Basel School of Design in the early 1950s and briefly worked for Armin and his wife Dorothea. Hanke became Weingart’s mentor, and went on to renounce the ‘antiquated’ graphic design practiced in Germany at that time.

On 22 March 1963, Weingart met up with Armin Hofmann to apply in person to become a student for the following year. After their meeting at Hofmann’s home, they drove to the school in Hofmann’s modest Volkswagen to meet with Emil Ruder, the school’s typography professor. Weingart was very impressed with the school — which was built in 1938 by Herbert Baur — and described it as being “dramatically modern. Enormous glass windows, free-standing and relief concrete sculptures by Jean Arp and Armin Hofmann graced the open courtyard and the foyer of the building. In his immaculate typeshop, Ruder had recently installed state-of-the-art facilities. In contrast to bleak and dreary postwar Germany, it all seemed incredible.” [1]. (Years later, in the 1980s, he himself would be the one to install the next level of state-of-the-art facilities, when he built up a brand new lab with Macintosh Plus computers for his students!) During the interview, Weingart thought that he was just applying to the school as a student, but was speechless when Ruder and Hofmann asked if he would eventually like to become a teacher at the school. Apparently there was something brewing in Basel.

Indeed, Hofmann and Ruder were in the process of starting up an international graduate-level graphic design program. In April 1968, when the Swiss Department of Education finally subsidized the program, Weingart went on to become professor of typography and graphic design of the ‘Weiterbildungsklasse für Grafik’ (Advanced Class of Graphic Design), an international master’s level program.

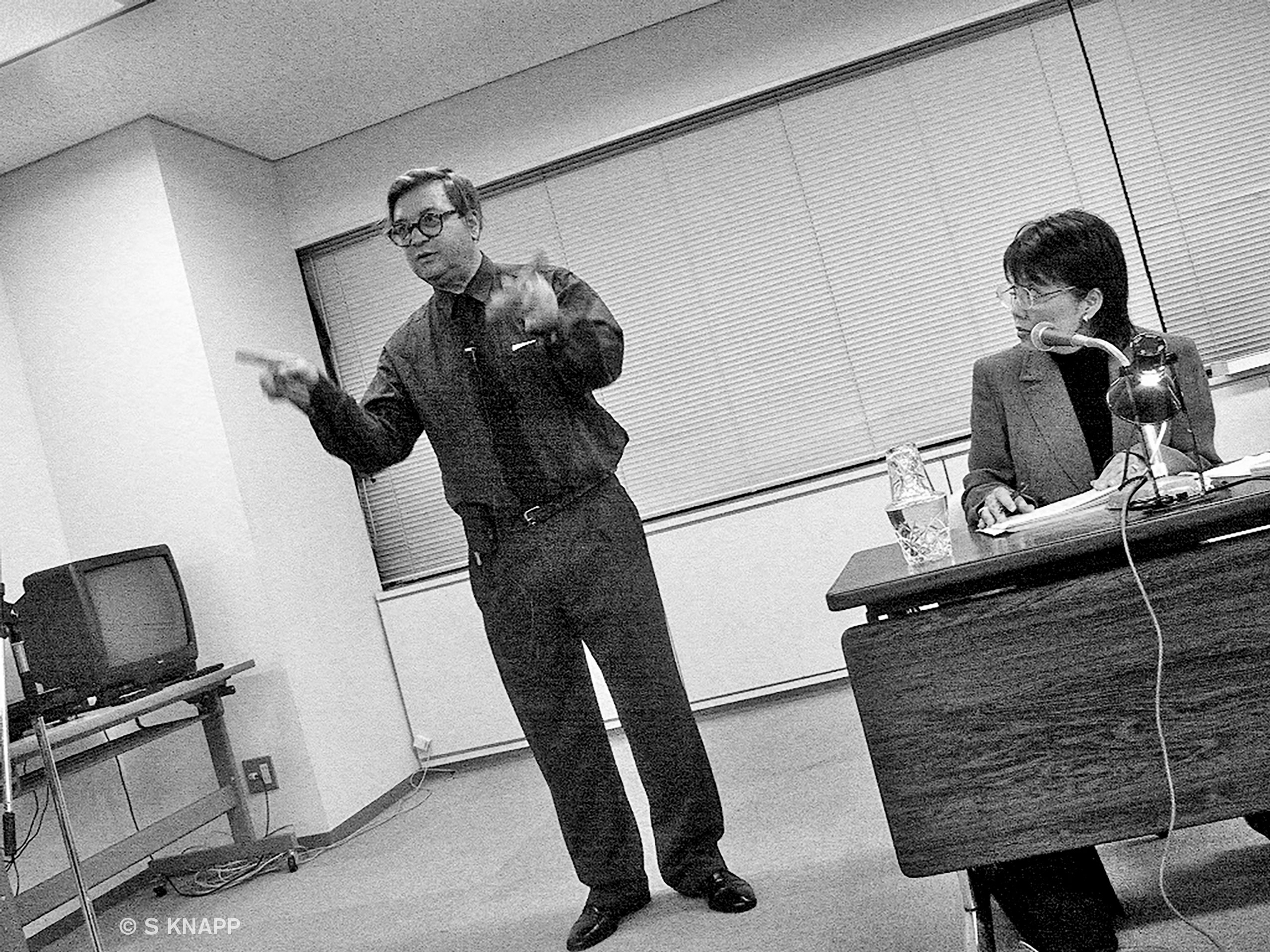

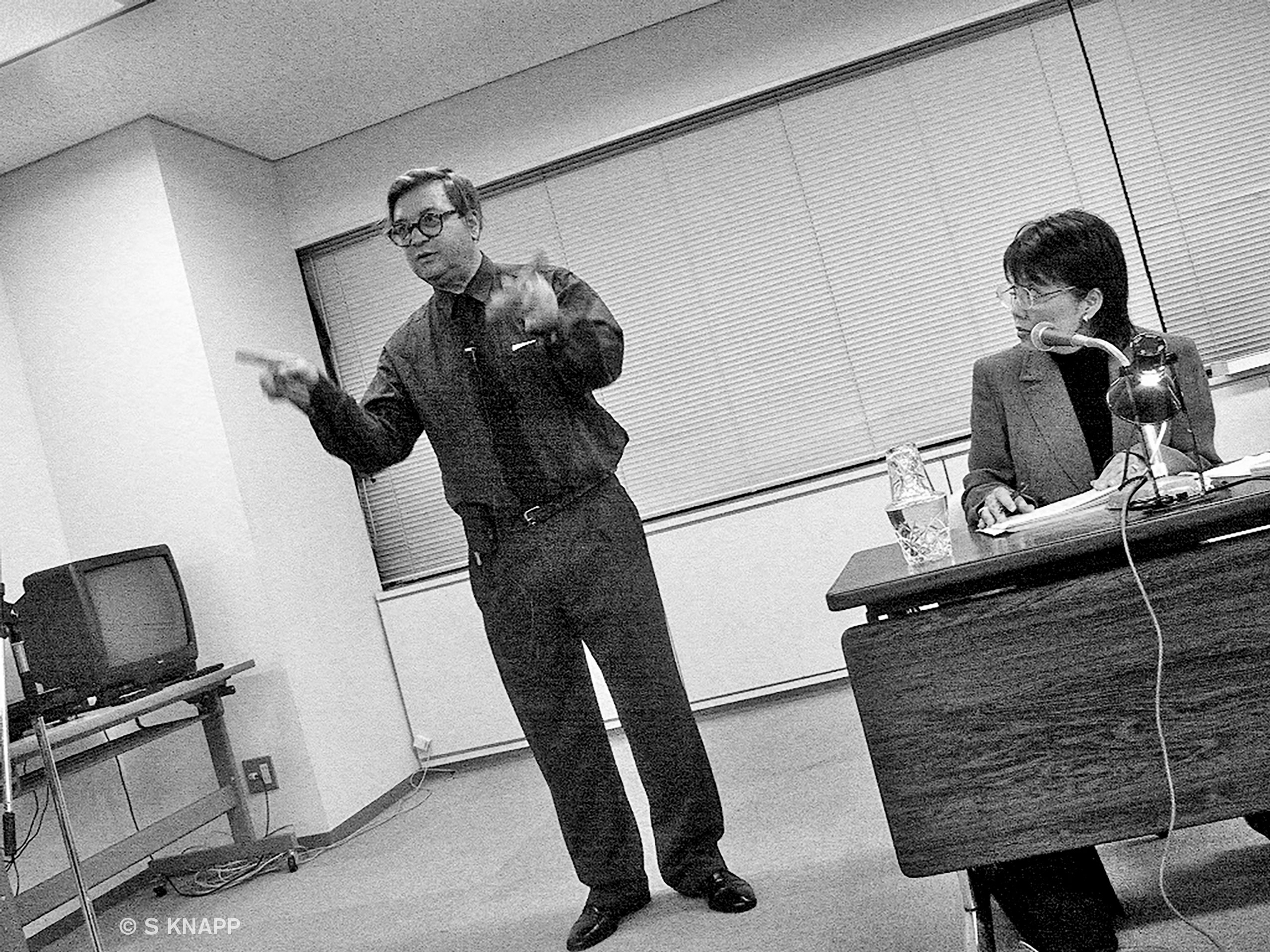

Lecturing at the DDD Gallery in Osaka, 2001.

In the meantime, in April 1964, Weingart began attending classes as an independent student. He had come to Switzerland to learn from Hofmann and Ruder, but soon became restless and could not sit still. He was able to find refuge in the typeshop and began experimenting with wood and metal type to create solutions for his independent classes. He came to realize that Ruder taught “like a dictator” and that his teaching methods “became banal with the same systems, always using the same typeface [Univers], and that the work was not artistic and not tailored to the individual.” [3] Basically, Ruder’s teaching wasn’t as crazy as Weingart had wished and he admitted that he had become quite bored with what the school had to offer.

From 1966 until 1968, Weingart worked part-time as an assistant typesetter and made two trips to Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. He was inspired by the landscapes, the old city walls and architecture, and he used his Rolleiflex camera to document what he saw. He later developed some personal projects using this imagery combined with typography. He was inspired by underground flyers made by students protesting the Vietnam war and the low standard of living in postwar Europe. His distaste for the typographic rules which he had to learn to become a professional typesetter also pushed him more and more to breaking the conventions. He annoyed teachers and designers inside and outside of the Basel School, and was slowly building up his reputation of being a rebel — with a very determined cause.

Dinner at the Zollstübli on the German border near Basel, 2011.

Wolfgang Weingart was one of the first to radically experiment with typography by actually bending hot metal type, setting it with the printing surface facing downwards, bundling handfuls of letters and putting them through his ‘Fournitures pour les Arts Graphiques’ (FAG) letterpress, stretching letterspacing, creating stepped text blocks, pushing the weight, size and expression of letterforms and words — as well as his critical step of moving from traditional metal type to the modern photomechanical processes in the darkroom.

He was able to create various bold versions of his typewriter type by manipulating the exposure of the stat camera, the large-format, vertical stationary camera which was used originally for just shooting film from camera-ready artwork. He would intentionally set the camera so that the type was out of focus or mount the film at an angle to the lens to create distortion and depth. He made interpretations of his own handwriting, which he described as “scrawling like an old grouch, struggling like a seven-year-old, writing with the uncertainty of a blind person, scribbling like someone who is impatient, or writing with the grace of a calligrapher.” [1]

At the Gasthaus zum Oschen, Oetlingen (Germany), 1995.

His unparalleled darkroom experiments were just as important as his on-going teaching of the Advanced Class in Basel, as well as the Yale Summer Program in Brissago. Weingart lectured extensively around the globe and his posters which implemented the techniques he developed became well known. He was living his dream to be an artist, creating exquisite collages of overlapping litho film, halftone screens and type. Each colour separation to be later used for offset printing was manually made using the stat camera, scissors and cellophane tape. He joked that lithographers would have considered his work to be “the result of professional ignorance”, but in reality it was absolutely groundbreaking. His radical ‘Swiss punk typography’ became a movement and paved the way for graphic design, which today may appear to be pretty commonplace with the abilities of modern computers — which however, were at that time non-existent.

Weingart’s quite original techniques connected his typographic, artistic and graphic work. He constructed type and then intentionally destroyed it, altering letterforms and text blocks, deconstructing function, challenging readability with his signature use of halftone screens, creating colour and tonal gradations using only the skill of his mind’s eye — it was impossible for him to know exactly how the offset printed pieces would look in the end, due to the limited technical possibilities of the darkroom. There were no printer’s proofs, no computer monitors, no colour laser printers. Mixing photography and typography according to his own recipe, he challenged the viewer in an extraordinary way, perhaps a way in which he had wished to be challenged in his early days at his chosen Basel School of Design.

Wolfgang Weingart was born on 6 February 1941 in the Salem Valley in Germany and passed away on 12 July 2021 in Basel. He was eighty years old. His ashes were laid to rest on 30 October 2021 in the forest on the Tüllinger Hill in Germany, near the Swiss border to Basel.

Visiting Ponta Delgada during the Azores Discussions, 2013.

—

Since 1988, Wolfgang Weingart was my teacher, mentor and friend. Just like any member of the family, he was quite stubborn in his younger years, but seemed to mellow with age. He would always ask how my life and work was going, exchange news and views on common friends and places, offer his wisdom on world news and politics. He enjoyed life and we shared many meals together, or a few beers or glasses of wine, just as a family would normally do. Because of him, my horizons have been greatly broadened, travelling to exquisite places such as Japan and the volcanic islands of Azores, honing my understanding of mankind and, last but not least, polishing my graphic design — finding the essence of a message, the precision in detail and learning great admiration and care for our tools of the trade.

Thank you for teaching me the art of being humble but strong, how to open up one’s heart to other cultures and to embrace and respect their traditions. Thank you for sharing your critical eye, your vast knowledge, not only in history and design. With your help, I was able to reach the next level — in life and in love.

Tschau, Bopp! See you tomorrow!

SK — All Saints’ Day, 1 November 2021/Basel.

—

References:

1

‘Weingart: My Way to Typography — Wege zur Typographie’. © 2000 Lars Müller Publishers, ISBN 3-907044-86-X

2

‘Weingart: The Man and the Machine. Statements by 77 of his Students at the Basel School of Design (1968–2004)’. With Essays by Susan Knapp, Michael Eppelheimer and Dorothea Hofmann. © 2014 Karo Verlag, ISBN 3-9521009-7-8

3

My personal interviews with Weingart, 2012–2018.

—

Photography:

All photos © by S. Knapp, except his childhood photographs which were given to me personally by Mr. Weingart.

Wolfgang Weingart, Tüllinger Hill vinyards near Basel, 2011.

Update — Wolfgang Weingart’s book is once again available: “Typography: My Way to Typography/Wege zur Typographie”. Lars Müller Publishers, 225 x 275 mm, 520 pp., 450 illust., softbound, EN/DE, 3rd edition, CHF 60.

Obituary as text file (15 KB)

Home

“I was born in a February. For the first thirteen years I lived in a beautiful valley near Lake Constance, the Salem Valley, in the southern-most part of Germany close to the Swiss border. It was the most important time of my life, and I have come to understand how the earliest years of life are the most decisive ones for individual and professional development. They are made of dreams and feelings only a child can experience.” [1]

Weingart in his early days.

With these words Wolfgang Weingart slowly draws us into his autobiographical masterpiece ‘Typography My Way to Typography — Mein Weg zur Typographie’. Weingart began work on this book in the autumn of 1994, which was then published six years later in 2000. The 520-page monolithic monograph contains a personal retrospective of his early life, artistic and typographical works, as well as his personal development as a designer. An authentic documentation of this gentlemanly provocateur, it is an invaluable source of inspiration for students and teachers of typography and graphic design.

In ‘My Way to Typography’, Weingart tells the story how his very early years were dramatically affected by World War II: “One night in the early spring of 1944, eleven months before the end of the Second World War, came the warning of another possible Allied attack. On the onset of the air raid, my mother and I headed in a frenzy for the deep, dark vaulted cellar to hide once again among the familiar cupboards, crates, and other curious contraptions. One of the most memorable ones was a wooden construction that was always in the same spot. It was the machine with which my mother made ice cream. The wooden tub held a cold mixture of natural ice and salt lick pieces that surrounded an internal steel vat with a built-in dasher to stir the cream. After thirty minutes of churning with the hand crank attached to the outside, the cream became cold and thick enough to eat.” [1]

As a child, this must have been a very comforting memory for him, every detail is crystal clear. And later in life, whenever dining out in the neighboring German towns with students and friends, Weingart would religiously order ice cream for dessert, topped off with a shot of locally distilled firewater — known in German as ‘Schnaps’ or ‘Träsch’. [2]

Weingart as a young boy, ready to hit the alpine slopes.

He vividly remembered the bombing and annihilation of the near-by town of Friedrichshafen in 1944 — precisely on April 28th — and was a witness to it’s dramatic aftermath. “Beyond the peaceful, silhouetted forest of our valley, a great pillar of fire mounted upwards and turned the nighttime skies to glowing red. Although only three years old and not realizing what had happened, I remember the fear like a permanent scar.” [1]

Weingart used his inner strength to heal from these traumatic experiences, to become resilient, to develop stability and learn to trust in his own beliefs. Many called him a rebel, but actually he was a survivor.

Wolfgang taking care a young deer.

In the spring of 1948, at the age of eight, he and his family moved into the castle of Salem, which was drenched in history: In 1098, it was established as an abbey of the Cistercians, a strict monastic order of the Catholic church according to the sixth century ‘Rule of Saint Benedict’. The residents were known as ‘black monks’, in reference to the colour of their religious habits, or costumes. As a result of the transition from church to state ownership, the abbey became a castle. What a dreamy place for a child’s imagination to develop!

Weingart’s mother was the resident physician at the castle and, besides having many chores to do, Weingart often entertained himself by spying on the aristocratic patients who visited his mother for medical treatments. “The keyholes to our rooms were just large and low enough for a small boy to comfortably observe the comings and goings of the international princes, princesses, duchesses, ladies, barons, and other honorable guests.” [1]

He and his mother however, lived in just two modest rooms of the castle, which were difficult to heat during the cold winter months, he remembered. Throughout his life, with a glint in his eye and a snicker on his face, he joked about the fact that he used to steal money from his mother — which finally ended on one occasion where he could not get out of bed for three days after being punished with “the dreaded wooden spoon”. Needless to say, he had a strict German upbringing, which later occasionally rubbed off on his style of teaching. [1] [2]

In 1954, he moved to Lisbon (Portugal) with his family and lived there for two years — “In contrast to war-stricken Germany, the foreign south embodied the fantasies of my childhood.” And upon visiting the nearby Spanish Mérida, his love for the Arabian culture started to bloom. His travels to the coastal city of Tangier (Morocco), with densely populated markets, mobs of veiled people and animals of all sorts, echoed his fantasy of how life must have been in the Middle Ages. According to Weingart, the cosmopolitan atmosphere with an abundance of shops with hand-lettered signs, custom tailors, and the tranquility of a relaxed city would later shape his design language.

Weingart on a field trip to Colmar with his students, 1990.

Although he was restless not knowing which direction life would take him, or how he would later make a living from his artistic passions, he was grateful to his parents for always encouraging him and eventually sending him to art school. In 1958, at the age of seventeen, he began a two-year program of applied arts and design at the Merz Academy in Stuttgart. He studied colour and drawing and discovered his love for linoleum and woodcuts, hot metal type and other various printing techniques.

In his free time, Weingart would work on his own projects, and because he was on good terms with the head of the school’s printing shop, he was able to use the facilities as he pleased. He helped out printing the school’s letterheads, invoices, student ID cards and other administrational forms. All of these experiences contributed greatly to a fundamental understanding of printing, which he would then later apply to his typography classes at the ‘Schule für Gestaltung’ — the Basel School of Design.

Students and teachers of the Advanced Class for Graphic Design, 1990.

In 1960 he began an apprenticeship as a typesetter at the Ruwe printing house in Stuttgart. Little did he then know that this five hundred year-old tradition was about to see radical transformations. Weingart admitted he was fortunate “to have had well-informed teachers who encouraged intense discussions and lively debate.” And it was here that he learned about the new ‘Swiss typography’ and designers such as Karl Gerstner, Emil Ruder, Armin Hofmann, Siegfried Odermatt and Carlo Vivarelli. The Basel School of Design and the ‘Neue Grafik’ design magazine had earned worldwide fame. Karl-August Hanke, a consultant at Ruwe, was one of Armin Hofmann’s first students at the Basel School of Design in the early 1950s and briefly worked for Armin and his wife Dorothea. Hanke became Weingart’s mentor, and went on to renounce the ‘antiquated’ graphic design practiced in Germany at that time.

On 22 March 1963, Weingart met up with Armin Hofmann to apply in person to become a student for the following year. After their meeting at Hofmann’s home, they drove to the school in Hofmann’s modest Volkswagen to meet with Emil Ruder, the school’s typography professor. Weingart was very impressed with the school — which was built in 1938 by Herbert Baur — and described it as being “dramatically modern. Enormous glass windows, free-standing and relief concrete sculptures by Jean Arp and Armin Hofmann graced the open courtyard and the foyer of the building. In his immaculate typeshop, Ruder had recently installed state-of-the-art facilities. In contrast to bleak and dreary postwar Germany, it all seemed incredible.” [1]. (Years later, in the 1980s, he himself would be the one to install the next level of state-of-the-art facilities, when he built up a brand new lab with Macintosh Plus computers for his students!) During the interview, Weingart thought that he was just applying to the school as a student, but was speechless when Ruder and Hofmann asked if he would eventually like to become a teacher at the school. Apparently there was something brewing in Basel.

Indeed, Hofmann and Ruder were in the process of starting up an international graduate-level graphic design program. In April 1968, when the Swiss Department of Education finally subsidized the program, Weingart went on to become professor of typography and graphic design of the ‘Weiterbildungsklasse für Grafik’ (Advanced Class of Graphic Design), an international master’s level program.

Lecturing at the DDD Gallery in Osaka, 2001.

In the meantime, in April 1964, Weingart began attending classes as an independent student. He had come to Switzerland to learn from Hofmann and Ruder, but soon became restless and could not sit still. He was able to find refuge in the typeshop and began experimenting with wood and metal type to create solutions for his independent classes. He came to realize that Ruder taught “like a dictator” and that his teaching methods “became banal with the same systems, always using the same typeface [Univers], and that the work was not artistic and not tailored to the individual.” [3] Basically, Ruder’s teaching wasn’t as crazy as Weingart had wished and he admitted that he had become quite bored with what the school had to offer.

From 1966 until 1968, Weingart worked part-time as an assistant typesetter and made two trips to Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. He was inspired by the landscapes, the old city walls and architecture, and he used his Rolleiflex camera to document what he saw. He later developed some personal projects using this imagery combined with typography. He was inspired by underground flyers made by students protesting the Vietnam war and the low standard of living in postwar Europe. His distaste for the typographic rules which he had to learn to become a professional typesetter also pushed him more and more to breaking the conventions. He annoyed teachers and designers inside and outside of the Basel School, and was slowly building up his reputation of being a rebel — with a very determined cause.

Dinner at the Zollstübli on the German border near Basel, 2011.

Wolfgang Weingart was one of the first to radically experiment with typography by actually bending hot metal type, setting it with the printing surface facing downwards, bundling handfuls of letters and putting them through his ‘Fournitures pour les Arts Graphiques’ (FAG) letterpress, stretching letterspacing, creating stepped text blocks, pushing the weight, size and expression of letterforms and words — as well as his critical step of moving from traditional metal type to the modern photomechanical processes in the darkroom.

He was able to create various bold versions of his typewriter type by manipulating the exposure of the stat camera, the large-format, vertical stationary camera which was used originally for just shooting film from camera-ready artwork. He would intentionally set the camera so that the type was out of focus or mount the film at an angle to the lens to create distortion and depth. He made interpretations of his own handwriting, which he described as “scrawling like an old grouch, struggling like a seven-year-old, writing with the uncertainty of a blind person, scribbling like someone who is impatient, or writing with the grace of a calligrapher.” [1]

At the Gasthaus zum Oschen, Oetlingen (Germany), 1995.

His unparalleled darkroom experiments were just as important as his on-going teaching of the Advanced Class in Basel, as well as the Yale Summer Program in Brissago. Weingart lectured extensively around the globe and his posters which implemented the techniques he developed became well known. He was living his dream to be an artist, creating exquisite collages of overlapping litho film, halftone screens and type. Each colour separation to be later used for offset printing was manually made using the stat camera, scissors and cellophane tape. He joked that lithographers would have considered his work to be “the result of professional ignorance”, but in reality it was absolutely groundbreaking. His radical ‘Swiss punk typography’ became a movement and paved the way for graphic design, which today may appear to be pretty commonplace with the abilities of modern computers — which however, were at that time non-existent.

Weingart’s quite original techniques connected his typographic, artistic and graphic work. He constructed type and then intentionally destroyed it, altering letterforms and text blocks, deconstructing function, challenging readability with his signature use of halftone screens, creating colour and tonal gradations using only the skill of his mind’s eye — it was impossible for him to know exactly how the offset printed pieces would look in the end, due to the limited technical possibilities of the darkroom. There were no printer’s proofs, no computer monitors, no colour laser printers. Mixing photography and typography according to his own recipe, he challenged the viewer in an extraordinary way, perhaps a way in which he had wished to be challenged in his early days at his chosen Basel School of Design.

Wolfgang Weingart was born on 6 February 1941 in the Salem Valley in Germany and passed away on 12 July 2021 in Basel. He was eighty years old. His ashes were laid to rest on 30 October 2021 in the forest on the Tüllinger Hill in Germany, near the Swiss border to Basel.

Visiting Ponta Delgada during the Azores Discussions, 2013.

—

Since 1988, Wolfgang Weingart was my teacher, mentor and friend. Just like any member of the family, he was quite stubborn in his younger years, but seemed to mellow with age. He would always ask how my life and work was going, exchange news and views on common friends and places, offer his wisdom on world news and politics. He enjoyed life and we shared many meals together, or a few beers or glasses of wine, just as a family would normally do. Because of him, my horizons have been greatly broadened, travelling to exquisite places such as Japan and the volcanic islands of Azores, honing my understanding of mankind and, last but not least, polishing my graphic design — finding the essence of a message, the precision in detail and learning great admiration and care for our tools of the trade.

Thank you for teaching me the art of being humble but strong, how to open up one’s heart to other cultures and to embrace and respect their traditions. Thank you for sharing your critical eye, your vast knowledge, not only in history and design. With your help, I was able to reach the next level — in life and in love.

Tschau, Bopp! See you tomorrow!

SK — All Saints’ Day, 1 November 2021/Basel.

—

References:

1

‘Weingart: My Way to Typography — Wege zur Typographie’. © 2000 Lars Müller Publishers, ISBN 3-907044-86-X

2

‘Weingart: The Man and the Machine. Statements by 77 of his Students at the Basel School of Design (1968–2004)’. With Essays by Susan Knapp, Michael Eppelheimer and Dorothea Hofmann. © 2014 Karo Verlag, ISBN 3-9521009-7-8

3

My personal interviews with Weingart, 2012–2018.

—

Photography:

All photos © by S. Knapp, except his childhood photographs which were given to me personally by Mr. Weingart.

Wolfgang Weingart, Tüllinger Hill vinyards near Basel, 2011.

Update — Wolfgang Weingart’s book is once again available: “Typography: My Way to Typography/Wege zur Typographie”. Lars Müller Publishers, 225 x 275 mm, 520 pp., 450 illust., softbound, EN/DE, 3rd edition, CHF 60.

Obituary as text file (15 KB)

Home